When if it’s not right, it’s terrible

During the Winter Olympics, I watched two German bobsledders compete against each other for gold and silver.

One of the pilots, Johannes Lochner, needed to catch the other, Francesco Friedrich, but his run wasn’t great, so he didn’t. And Friedrich also happened to be the most dominant bobsled pilot of his generation.

Even though they were only fractions of a second apart, the commentator said, “you know, Johannes will likely refer to that as a ‘terrible’ run.”

And as I watched, I thought, “yeah. Because it was terrible.”

It occurred to me that I refer to things as “terrible” a lot. Things that someone else might simply characterize as mediocre, fine, or even pretty good. Like the second best run at the Olympics.

But I’m not trying to be hyperbolic. It’s just that in the upper echelon of the sports world, sometimes either you win or you’re terrible.

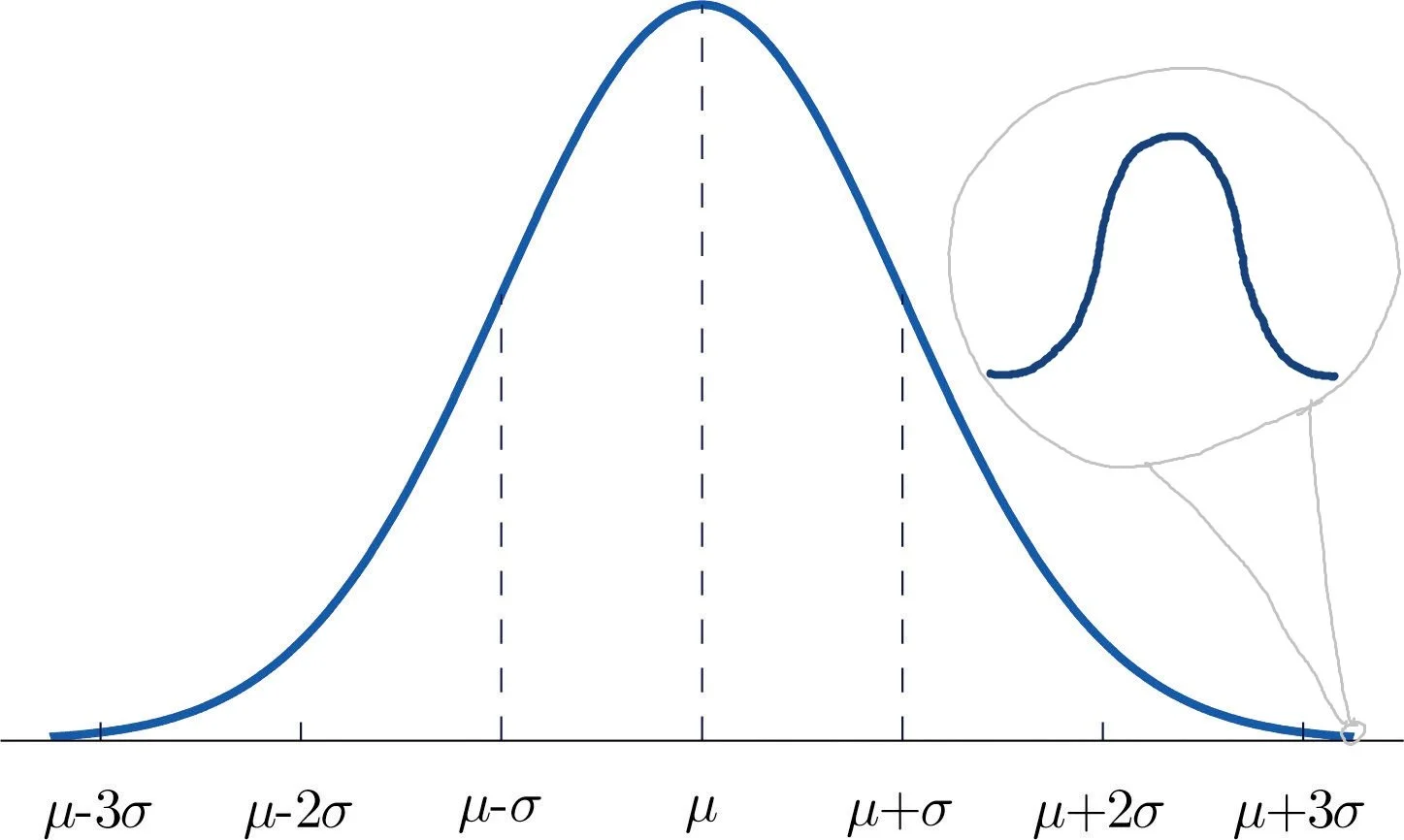

If you imagine athletics generally in life, there’s a bell curve. And the Olympics sit, athletically, on this little edge. Of course, they’re the stand-outs. Everyone competing is remarkable.

But when you take that little edge and you zoom in on that little edge there's another bell curve.

And in this niche bell curve, there's a whole bunch of people in the middle. And then there’s these people at the end of the curve.

The standards in that little tiny niche within that tiny niche are really, really high.

And when you’re at that point, you’re competing to win. Anything else is, in the moment, a total failure. Because there is no in-between: either you win, or you don’t. And not winning is terrible.

I know what it’s like to compete at the Olympics and fail. My team and I took seventh, while the world watched.

And I get it: on that big bell curve, being seventh in the world is an achievement. But for us, it was awful. It sucked. It was terrible. And I wasn’t happy with anyone who called it otherwise. 16 years later I still think it’s terrible and I want it back.

And that terribleness spurred us on to come back stronger, leverage that pain, and take the win four years later.

This might sound super specific to athletics or the most competitive environments in any genre but in my experience, there are moments in all of our lives when anything short of success simply won’t do. Moments when if we don’t nail it, we may as well have stayed home.

Sometimes, “good enough” really ISN’T good enough.

I see something happen in certain leadership circles where people who are making big, important decisions sort of shrug their shoulders if decisions weren’t quite right. They’ll make excuses for it, like, “well, we made the best decision we could at the time.”

What I would like us to understand is that in extraordinary circumstances, decisions need to be right.

Sometimes we cannot afford to get decisions wrong, or to fall short. We can not afford to be cavalier about making an imperfect decision.

Obviously, this is not a mindset we can afford to have ALL the time.

We don’t want to teach our employees or teammates that anything short of perfection or winning is terrible. And we don’t want to berate ourselves every time we screw up. After all, a growth mindset is a big factor in long term success, and happiness.

If you know me, you know I am all about leveraging failure in order to learn and come back better. It’s part of our culture at Classroom Champions and I’m very proud that our organization scores incredibly high year-in and year-out on third-party culture surveys around our people feeling that it’s ok for them to fail. (Huge shoutout to Jayson Krause and his team at Level 52 and Jonathan White at Improve Consulting Group for lending their support!)

But I am a firm believer that if we’re at the crux of something, a crucial moment in our life or career, or when we’re really going BIG on something — we need to commit everything we’ve got to get things right.

That's not the way you want to live every day, and it's not the way you parent or lead regularly, but when the pressure is on and the screws tighten, it might be necessary.

Sometimes we have to say to ourselves “well, that was terrible,” and then try to do better next time.

- Steve